Over this past weekend, I flew back to my hometown of Penang to conduct an Introduction to Web Development workshop with TechLadies, a community initiative founded by Elisha Tan for women in Asia to connect, learn, and advance as programmers in the tech industry. Although I was born in Penang, my family moved down south to Johor when I was 4, so technically I didn’t grow up in Penang.

However, my family identifies very strongly as Penangites. My parents had lived there their whole lives prior to the move, and so did my grandmother (who lived with us too). My older siblings obviously had clearer memories of growing up in Penang, while I had hazy memories of our old house at Balik Pulau.

We spoke almost exclusively Penang Hokkien in our household. For the benefit of non-Chinese readers, Hokkien is a Chinese dialect that originated from the Minnan region, which is located in the south-eastern part of the Fujian province in China. Timothy Tye has written a comprehensive article on Chinese immigration to Penang, as well as his theories on the origins of Penang Hokkien, which are both worthy reads.

Anyway, in spite of the fact we were physically not in Penang, home and being with my family meant Penang, for as long I can remember. I often joke with my friends that I can remember my mum teaching me to read in English and my grandma teaching me to write Chinese, but I came out of the womb speaking Penang Hokkien.

Given both my parents were teachers, some people (and school teachers) have expressed surprise when they discover our language of choice at home was Penang Hokkien. It did not seem to have hindered our ability to be fluent in other languages, apparently.

Feelings I didn’t know I had

I never gave languages a second thought when I was younger. Words, regardless of language, were just a way for me to express what I thought and felt. Kids being kids, I just spoke whatever language was the predominant one at that point in time. Nobody cared about English, Chinese or Malay when we were being chased by the “catcher”.

Although, I did notice that the Hokkien I spoke was quite different from the Hokkien spoken in Johor and Singapore. We pronounced words differently, and used different words altogether sometimes. The intonations were also quite distinct, and I would just say, well in Penang, our Hokkien is different.

A few years ago, I discovered the Penang Hokkien Podcast and when I first heard it, it was a surprisingly emotional experience. People who grew up their whole lives in a community that spoke the same mother tongue as themselves would probably find this hard to relate to, but it really was something else to hear my mother tongue streaming out of the speakers of my computer.

I never realised this before, but I guess on a subconscious level, I always associated Penang Hokkien with home. Because I only heard it when I stepped into my house, when I spoke to a family member, when I returned to Penang. It’s hard to put into words but to hear more than an hour’s worth of Penang Hokkien from a podcast, it was all the feelz.

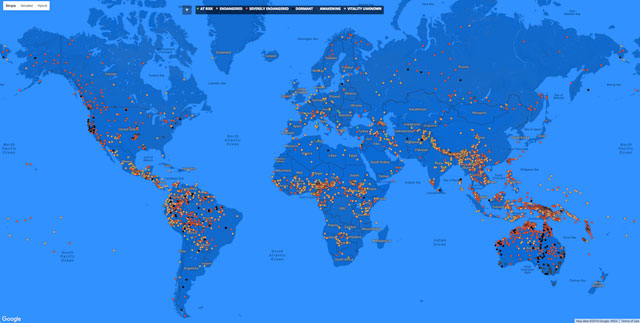

Languages are going extinct

Languages have always been an area of interest for me. Languages, writing systems, typography. To me these are methods that humans developed to convey ideas amongst ourselves, and the fact we have more than 7000 languages still being spoken today is a testament to the diversity of human history and culture.

When I was in school, I only had a handful of friends who spoke dialect at home. Kids from my generation who grew up in Singapore were the outcome of the campaigns launched by the government back in the 60s and 70s, to eschew dialects in favour of more “practical” languages like English and Chinese. Many of my friends only heard dialects being spoken when they visited their grandparents, barely enough exposure to become fluent.

And now that my friends have kids of their own, this new generation has even less chances of being exposed to their dialects. In fact, English has become so dominant in Singapore that fluency in mother tongues like Chinese and Malay has deteriorated among the younger generation. Personally, I find this tragic.

In the past couple of years, I’ve read numerous articles about how Penang Hokkien may be slowly dying out, and it’s alarming to me. Alarming because something I associate so strongly with the idea of home, and of belonging, is gradually fading away.

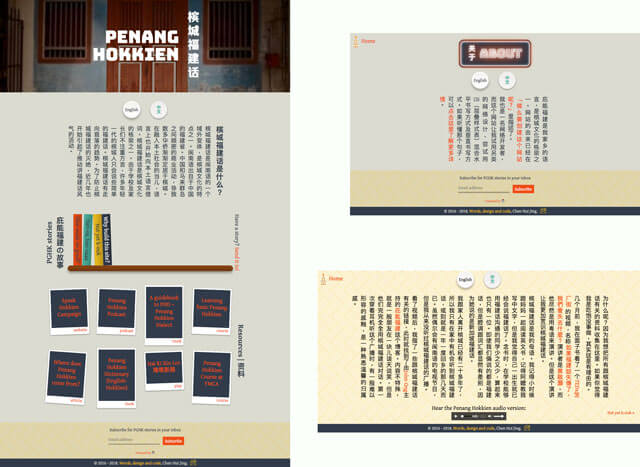

Which is the reason why I created a website called Penang Hokkien 槟城福建话. I found that there are certain words or phrases that are only used by people who speak Penang Hokkien. In addition to recording these words and their usage in daily speech, I also wanted, wherever I could, add some anecdotes about the etymology of such words and phrases.

All technical details about the site can be found in an earlier post, where I explain all the fun stuff I got to use to build the site, as well as the challenges with implementing a writing-mode switcher in addition to being bi-lingual.

Encourage creation of local content

Language can and does affect the way we perceive the world around us, and how we think about problems. I can understand the practical aspects of there being a “universal” language to facilitate global communication, but not at the expense of losing a large variety of perspectives.

More than 50% of websites on the web are in English, while only 5% of the world’s population are native English speakers. To me, there’s something not quite right about this ratio. Yes, the computing age started out from English-speaking regions and took off from there, but as more and more of our communications move onto the digital realm, it is important that we preserve language diversity.

Languages are representative of human heritage, and convey unique cultures. If you speak more than one language, then you can probably understand that there are certain concepts that simply get lost in translation as you switch from one language to another.

Studies done by the Internet Society have shown that while cost of access is a barrier to getting people online, many non-Internet users claim that the Internet is simply not relevant or of interest to them. If the Internet is meant to enhance the free flow of information and ideas across the world, then creation of content on the web should not largely be limited to English-speaking communities.

I have been privileged to have the opportunity to speak at conferences all around the world over the past 2 years about East Asian typography and web layouts. Because most of the audiences I speak to are not native English speakers, I make it a point to encourage the creation of local content. To show how web technologies have improved and are still improving in order to allow every writing system in the world to be correctly rendered on the web.

Wrapping up

Will the ratio of content on the web match that of the physical world? I have no idea. But I believe that if we don’t do anything about it now, then this gap will just continue to grow. I’m aware I don’t have a huge following, nor am I much of an influencer, however, if I can get 1 more person to create content in their local language, that’s 1 more than if I didn’t try.

For a better web, I say. 💪