So for 2018, I got myself some gainful employment doing full-time frontend development work. You know, the kind where you go to an office, and have colleagues and bosses? Also, pay cheques and CPF (that’s the Singapore equivalent of a retirement fund), love those. 💰💰💰

Anyhow, one of my responsibilities was to refactor and clean-up the frontend codebase for the company’s existing products. It’s not that I’ve never refactored codebases before, half my career was built on refactoring legacy projects, but these were a bit larger and messier than my previous projects. And note that I used the word products, with an ‘s’.

But first, some back-story.

- Start-up founder has great idea.

- Start-up founder throws together prototype with some interns to show potential clients

- Potential clients become actual clients

- Actual clients make feature requests

- Interns add features the best they can

- Product

I believe such a situation is far from uncommon, and pretty much every start-up you throw a stone at has some similar history. So I’m not throwing shade at my employer at all. In fact, I admire the fact that they executed a great idea with limited resources, and managed to on-board actual paying clients. Much kudos for that.

Assessing the situation

I was informed, before joining the organisation, that the code base needed work. Things worked, but under the hood, it was getting unmanageably messy with increased throughput and piling feature requests. And with that, I decided a general strategy was in order before any actual coding or refactoring was to take place. I thought a 3-phase approach could work for this instance.

By the end of my engagement, phase 3 was still quite far away because there were significant architectural changes required for the entirety of the application. But hey, phase 2 (clean-up) alone was already a significant endeavour.

I hadn’t had much experience with Python applications prior to this, but I’ve come to realise that certain patterns are prevalent when it comes to web applications. The product that I had to tackle was built on Flask, and since I was hired for a frontend role, almost all my work took place exclusively in the static and templates folders. Almost.

# Structure of a basic Flask application

PROJECT_FOLDER/

|-- yourapplication.py

|-- static/

| `-- style.css

`-- templates/

|-- layout.html

|-- index.html

|-- login.html

`-- …Given that I was the first dedicated frontend role they ever hired, it was no surprise that the state of the project’s frontend was, how shall we put this, left wanting. Apparently, the backend of things wasn’t much prettier, but again, I doubt most start-ups have well-architected codebases until later on in their lifespan.

Preliminary site assessment

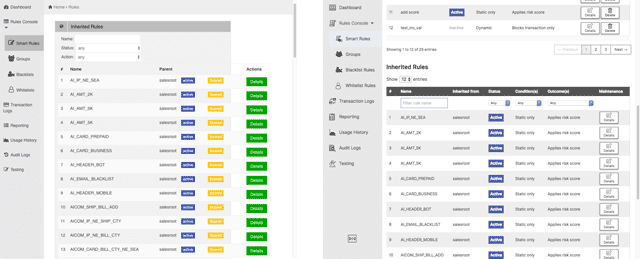

Before diving into the code proper, I did a basic click-around, to get an idea of the look and feel of the site, and what it did. To me, this was a pretty important step, because you can only encounter a site for the first time, once in your life. And I took notes. Notes on things that took me a while to figure out, places where I had to ask “hmmm, now what does this even mean?”, functionality that required extra cognitive effort to comprehend.

As someone who has been building interfaces for a living over the past 5 years, believe me when I say, people who work on the product itself on a daily basis are the worst group to do user testing with. Because we interact with the product, bugs and all, way more frequently than normal users.

Hence, we inadvertently become blind to numerous usability issues simply because whatever we do to workaround the issue, has been committed to muscle memory. Even if it’s something unintuitive, like having to click certain things in a specific sequence for it to work.

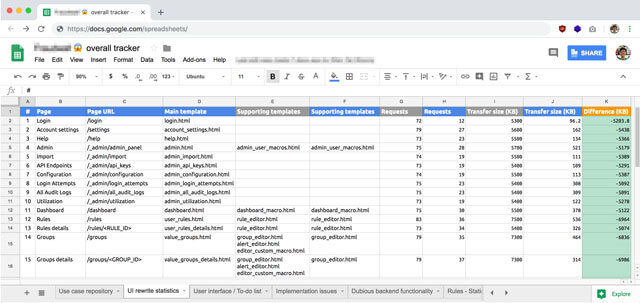

All of this was documented into a trusty spreadsheet. I don’t know about you, but I’m rather fond of spreadsheets as an organisational tool. To me, it’s the easiest way to organise data into useful information. But that’s just me. You do you.

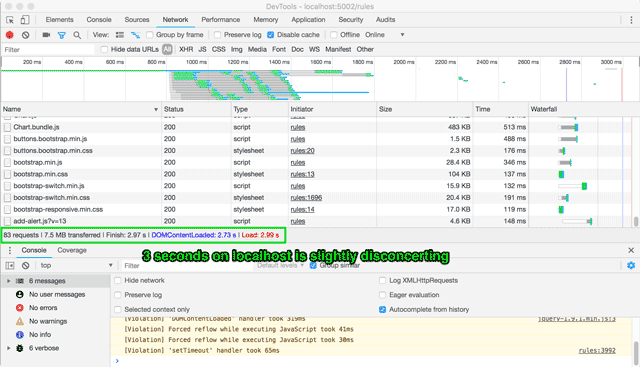

Site analysis with tools

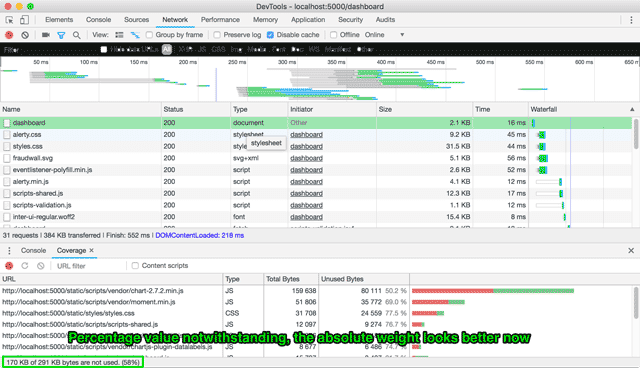

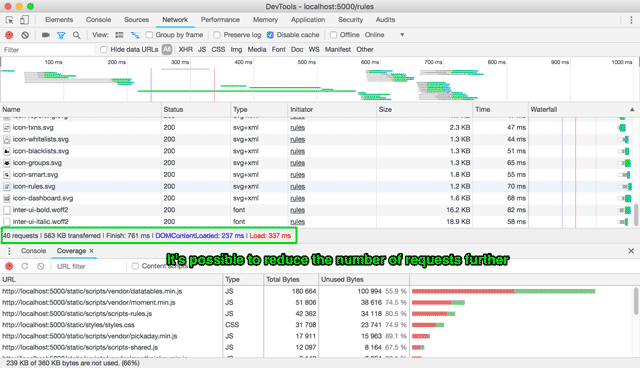

The most basic analysis can be done via DevTools in any of the major browsers from the Network tab. It’s more of a personal preference, but I prefer how Chrome and Firefox do it, where both of them tell you the number of requests, size of transfer, time it takes to finish loading, and when DOMContentLoaded is fired.

After working through the entire product, I came up to a total of 24 different pages, some ranging from pure textual content to others with a whole lot of business logic for creating complex rules and conditions. I tossed my findings into the aforementioned spreadsheet and ended up with the following statistics:

- Average number of requests: 76

- Average page weight: 6.017mb

- Total number of external JS libraries: 49

- Total number of external CSS files: 30

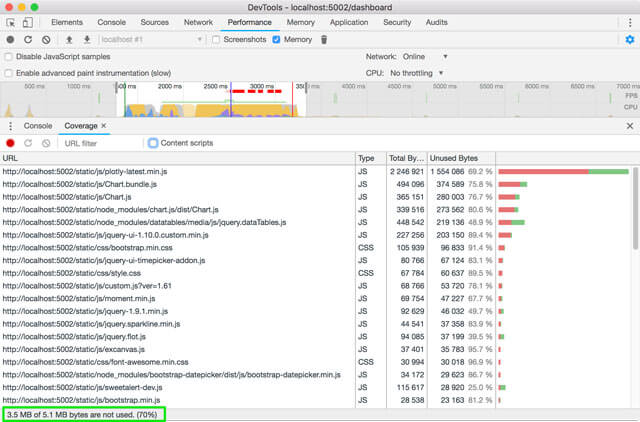

Chrome also has a nifty code coverage tool that gives you a general idea of how much redundant code is present in your application. Usually the biggest source of redundant code comes from external libraries, but sometimes this is inevitable, so it’s necessary to look deeper than just the raw numbers themselves.

Evaluating audit results

It became clear that any attempt to refactor the code would take significantly more time and effort than I could afford with my one-woman team. I call this the one-brain-two-hands problem, i.e. Hui Jing only has 1 brain and 2 hands.

Data from the backend was being passed to the frontend via Jinja variables. On occasion, some of the variables were not simply raw data, but contained preformatted strings and values that made it tricky to change the way things were implemented.

There was a large amount of inline Javascript in the template files, where Jinja variables were directly called and used within Javascript functions between <script> tags. That was a hard no for me, and I insisted on extracting all Javascript into separate .js files and keeping the templates clean of inline styles and scripts.

Burn it down, build it up

To be honest, I wouldn't recommend this approach lightly. But given the circumstances, that:

- it wasn't too large an application

- there was no proper HTML structure at all

- external libraries were outdated and installed inconsistently

- the code was a hodgepodge of Jinja variables in inline scripts and inline styles and

- there was the fact that my youth was slipping away,

I decided to rip out all the styles and scripts and rewrite them from scratch, only including external Javascript libraries, like Moment.js and Chart.js, where necessary.

Although my team was comprised of my left hand and my right hand (and also my brain, a very important member of the team), I was reasonably confident I could pull this off because I can CSS faster than most developers I know, so the look-and-feel part of things wouldn’t take me too long. From a UI functionality perspective, things didn’t appear to be overly complicated.

Even so, it probably took 5 full man-months worth of effort to finish up the initial rewrite, housekeeping and documentation work. In the meantime, there were also demos to be built (for tradeshows and the like), as well as my own non-employer related commitments. So it’s safe to say I kept busy for the past 8 months.

Function matching

I’d like to say there were functional requirements that I could refer to when doing the rewrite, but unfortunately, there were none. Or at least none that were updated to reflect how the product functioned in its current state. But if all was well, I wouldn’t have gotten the job now, would I?

Plan B: run an instance of the application that tracked the current master release and match all observable functionality as I rewrote every page of the application. I would like to reiterate that this worked only because the application was of a manageable size to begin with.

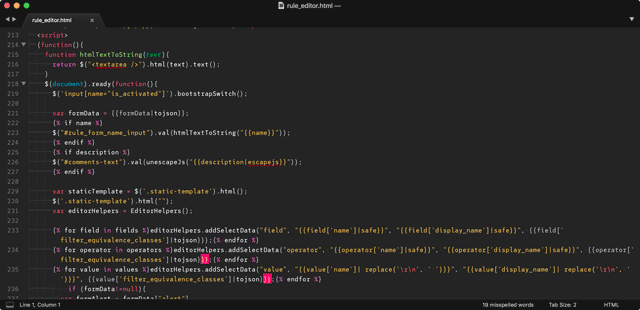

This approach also flushed out a large number of implementation issues. for example, there were limited REST APIs by which to access information stored in the database, because the previous implementation used Jinja variables directly into inline Javascript functions. See exhibit below:

<script>

(function() {

$(document).ready(function() {

$('input[name="is_activated"]').bootstrapSwitch();

var formData = {{ formData|tojson }};

{% if name %}

$("#rule_form_name_input").val(htmlTextToString("{{ name }}"));

{% endif %}

{% if description %}

$("#comments-text").val(unescapeJs("{{ description|escapejs }}"));

{% endif %}

var editorHelpers = EditorHelpers();

{% for field in fields %}editorHelpers.addSelectData("field", "{{ field['name']|safe }}", "{{ field['display_name']|safe }}", {{ field['filter_equivalence_classes']|tojson }});{% endfor %}

{% for operator in operators %}editorHelpers.addSelectData("operator", "{{ operator['name']|safe }}", "{{ operator['display_name']|safe }}", {{ operator['filter_equivalence_classes']|tojson }});{% endfor %}

{% for value in values %}editorHelpers.addSelectData("value", "{{ value['name']| replace('\r\n', ' ') }}", "{{ value['display_name']| replace('\r\n', ' ') }}", {{ value['filter_equivalence_classes']|tojson }});{% endfor %}

if (formData!=null) {

var formAlert = formData["alert"]

if (formAlert) {

editorHelpers.populateAllAlertData(formAlert);

}

}

var groupObjs = [];

/* Another 200 plus lines of this */

</script>There was also several instances where the data passed to the frontend contained embedded markup, which sort of forced me to modify the Python application files to remove the unwanted pre-processing. So much for leaving the backend alone. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Re-evaluating site performance

When the smoke cleared, the statistics of the site were as follows:

- Average number of requests: 30

- Average page weight: 311kb

- Total number of external JS libraries: 15

- Total number of external CSS files: 4

A lot of the weight came from full-featured external libraries whose functionalities were barely used. A large amount of that was either replaced with lightweight alternatives or rewritten from scratch.

The only external CSS loaded were for datepickers and datatables, and even those were customised to include only the relevant styles, so there were a lot of savings on the CSS side of things as well.

As a preliminary assessment, this was a relatively good outcome. There is further room for improvement for a second-pass refactoring, both on the Javascript side as well as the CSS side, but that portion of work will probably fall to the next person who takes over this project.

Wrapping up

The best analogy I had for this experience was swapping engines on the a flying plane. But I don’t think such situations are an uncommon occurrence, especially in the world of start-ups. I did learn quite a lot from the experience (even picked up a little Python along the way), and not just from a coding perspective.

Paying off technical debt is not a trivial endeavour at all, and it highlights the importance of having a solid architecture in place before any lines of code are even written. As several experienced seniors have once advised me:

The best code is the code not written

Documentation appears to be another thing that takes a back-seat in start-ups, but the fact is that people will come and go. In an environment with a relatively high attrition rate, proper documentation and handover becomes even more critical to ensure continuity and consistency of the software you’re building.

In an ideal world where unicorns shit rainbows, we wouldn’t have to do such major rewrites or refactoring projects, however, given that every organisation has their own set of constraints, sometimes it is just an inevitable part of the product development process.

Here’s to constant improvement, and may the code you write always be better than what you wrote yesterday. 🥃