It is not a secret that I am a huge fan of Singapore’s national libraries. Their selection of books and resources is amazing, with an excellent nation-wide system that makes borrowing and returning books unbelievably convenient. They even fulfil book requests! It’s not a fake form that gets submitted to the ether! 🙆

I could go on and on, but the point of today’s post is to talk about one of the best exhibits I’ve been to in a long time. There’s an exhibit going on at the National Library Building called Tales of the Malay World that showcases a glorious collection of Malay manuscripts and early books. It started running from 18 August, 2017 and will end on 25 February, 2017 (if you’re reading this after it ends, I’m sorry, but I hope this post can give you a small taste of it).

Some background on the Malay language

Malay had been serving as the lingua franca of the whole Malay Archipelago for many centuries. According to Teeuw (1967), inscriptions of Old Malay dating back to the second half of the 7th century have been discovered. Malay had been the official court language of the Shriwijaya empire, and it served as the language of trade amongst foreigners in the region, as well as between Indonesians of different native tongues.

The exhibit opens with a bit more background about the history of the Malay language if you’re interested. Also, if you can get your hands on them, I found the following books and essays by Andries Teeuw to be quite comprehensive:

- Modern Indonesian Literature

- The history of the Malay language. A preliminary survey

- A Critical Survey of Studies on Malay and Bahasa Indonesia

The manuscripts section

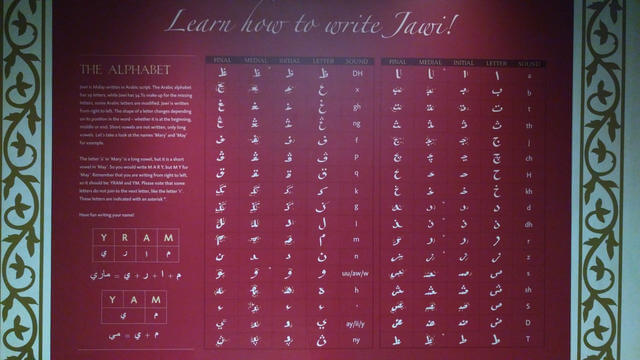

We start off with manuscripts, and some of them are on loan from the British Library (well, if you’re not from Southeast Asia, FYI Western Europe colonised the shit out of our region 🙄 moving on…), while others are from the National Library’s own collection. Almost all the manuscripts and books were written in the Jawi script.

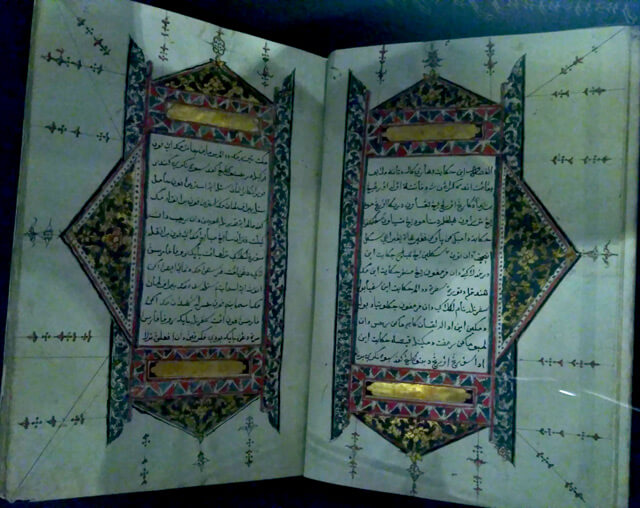

As an aside, I had taken the Coursera MOOC on Deciphering Secrets: The Illuminated Manuscripts of Medieval Europe because that’s my sort of thing, but I hadn’t really seen illuminated manuscripts in real life. Until now. 😲

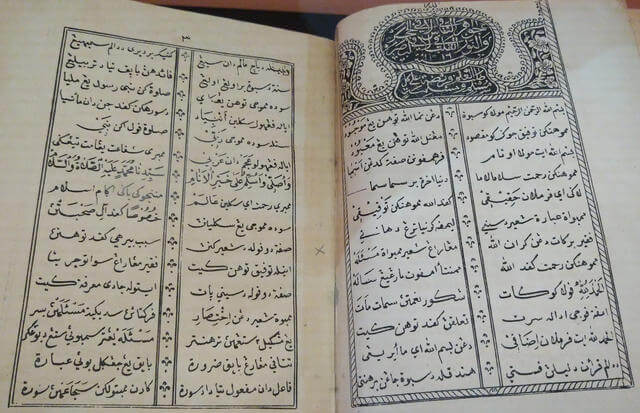

Not every manuscript in the exhibit was illuminated, but I found the Jawi script, and Arabic scripts in general, to be extremely elegant and beautiful. It’s hard to put into words, but every script feels like a different persona to me.

To me, Han characters and the Chinese script have a balanced quality of strength and grace (that’s the best translation I could muster of 柔中带刚, please offer a better one if you can). Arabic scripts are romantic and refined, sprinkled with a bit of whimsy.

I recently purchased a copy of Cultural Connectives by Rana Abou Rjeily to learn more about the Arabic script. I highly recommend it for non-native Arabic speakers trying to start learning Arabic.

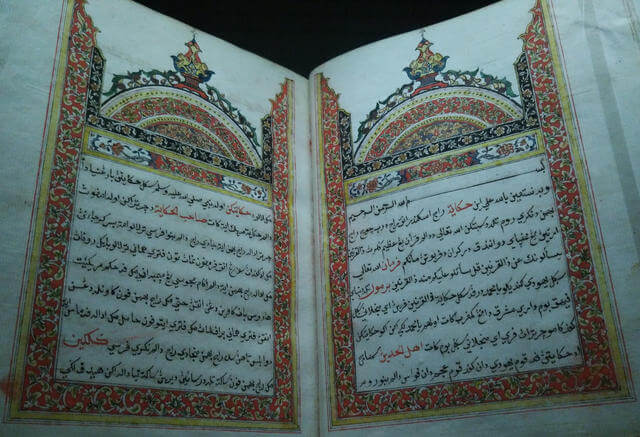

Not every manuscript on display was an illuminated manuscript. Most manuscripts that were meant to be read aloud to local audiences were plain, and only those that were collected or copied for European collectors were ornately decorated.

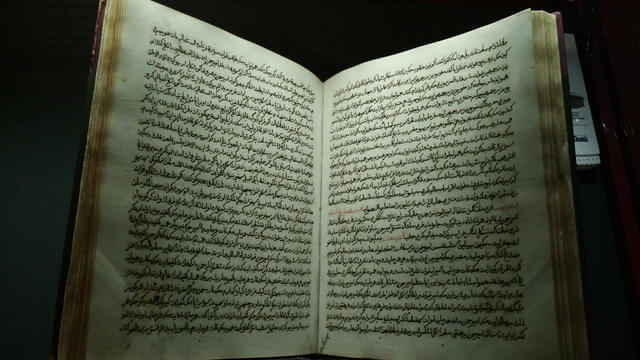

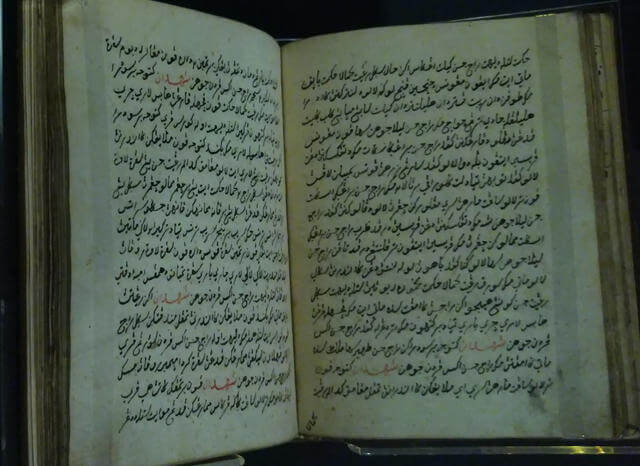

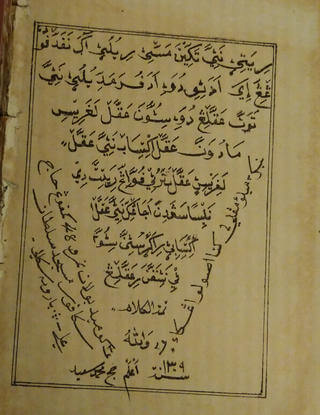

But even the so-called “plain” manuscripts are beautiful because every manuscript is unique, created under the pen of their respective copyists, reflecting their individuality with every letter and flourish.

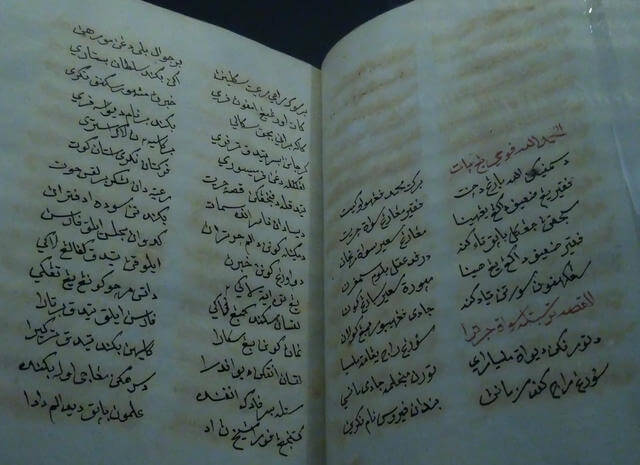

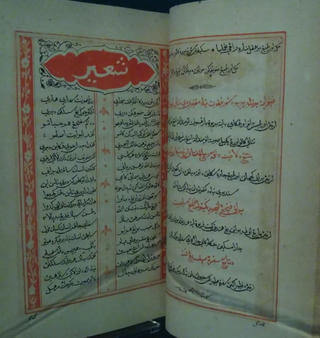

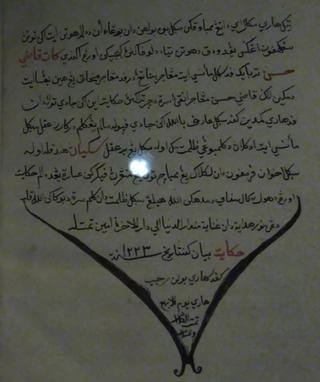

Most of the manuscripts on display were Hikayat (حكاية), which are narrative stories, and Syair (شعير), which are a form of traditional Malay poetry.

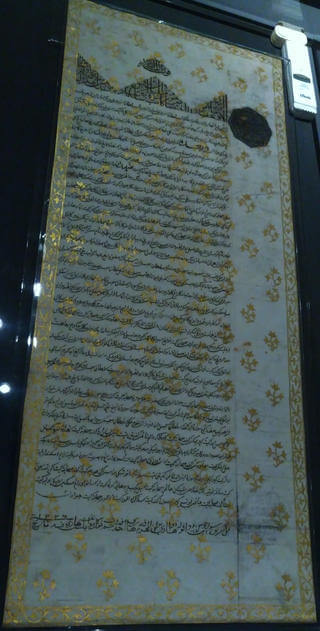

One of the highlights of the exhibit (it was on the brochure!) was this huge illuminated letter from Sultan Syarif Kasim to Raffles, where the Sultan request for British support against the Sultan of Sambas. I don’t know about you, but if I received a letter of this size, I’d say the author really wanted to get his point across 😆.

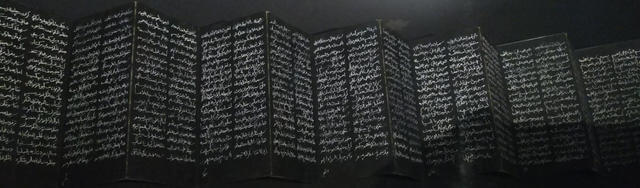

Another really cool manuscript I liked was Syair Dendang Siti Fatimah. It takes the form of a folding book, reminiscent of Chinese folded books (折本), and is, by my estimate, at least 1.5 metres long.

This style of manuscript is typical of those from Thailand and Myanmar and was written in Pattani (southern Thailand). It consists of two poems: Syair Dendang Siti Fatimah and Syair Masihat Kepada Laki dan Perempuan.

The printed works section

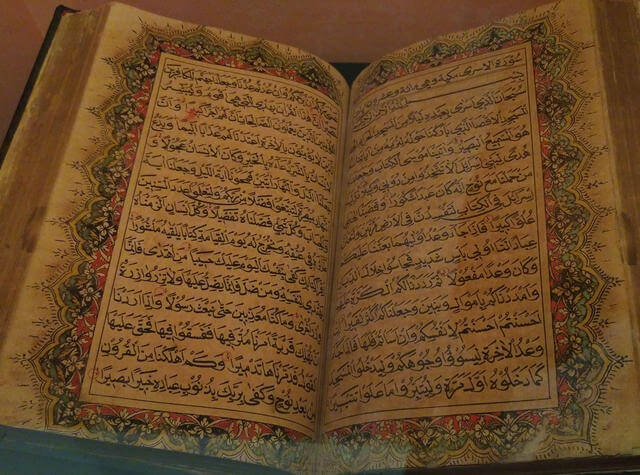

Malay/Muslim printing had been around in Singapore from 1860 and Singapore was an important hub for Malay literary printing. According to the exhibit, the earliest known book published by a Malay/Muslim printer in Southeast Asia is a Qur’an printed in Palembang in 1854 using a lithographic press that was purchased from Singapore.

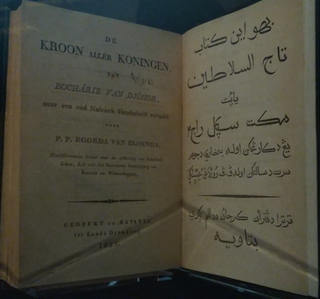

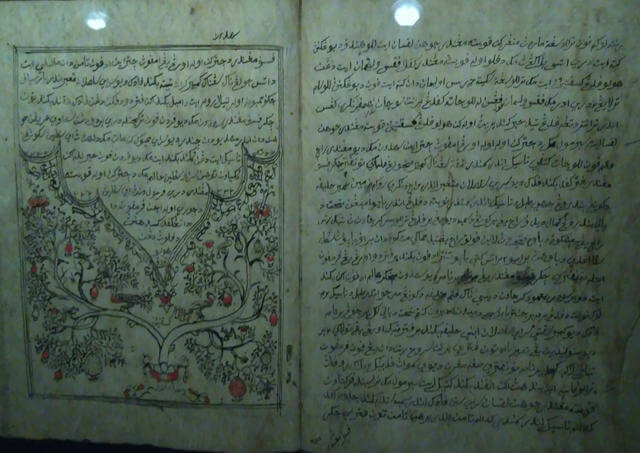

Lithography was the technique of choice, and this I presume was due to the complexity of the Jawi script (Arabic scripts, in general). It served as an alternative to manuscript culture, and made printed texts more accessible to the masses.

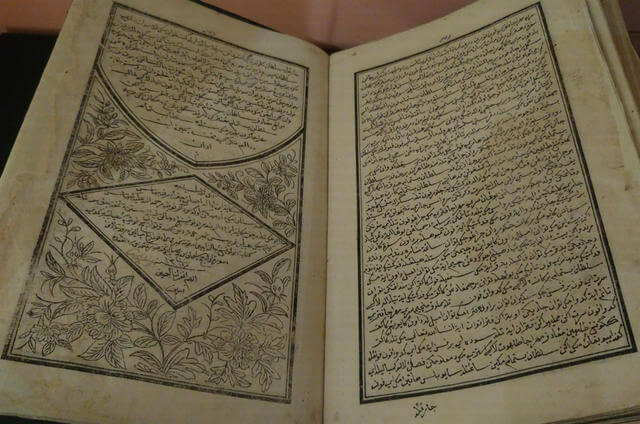

Cermin Mata, which is the image on the right above, is considered one of the most attractive examples of early lithographed Malay books that managed to imitate the flow of handwritten scripts and the artistic style of Malay manuscripts. Contrast that with the image on its left, which was printed by letterpress.

What really got me was how beautifully designed the layouts for these manuscripts and books were. It wasn’t just all just a single rectangular block all the time.

Then again, maybe the curator just turned to those pages that were specially laid out. I’m actually not sure, but point is, there were lots of creative layouts on display.

Qur’ans

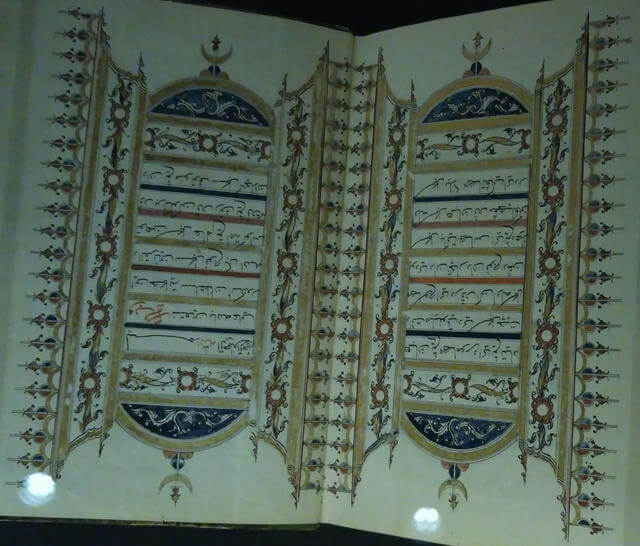

The Qur’an is the central text of the Islamic religion, which Muslims believe to be the last revealed word of Allah and is widely regarded as the finest work in classical Arabic literature.

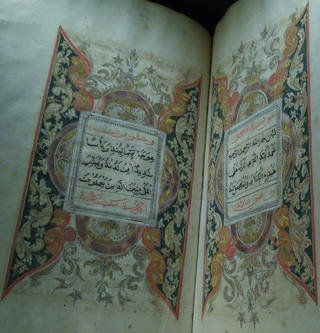

According to the exhibit, Qur’ans all over the world, if decorated, would have the decorations at the beginning of the book. But Qur’ans found in Southeast Asia feature three decorated double pages - at the beginning, middle and end of the book.

The following Qur’an is possibly the second-earliest lithographed Qur’an printed in Singapore, and it too contains three decorated double pages at the beginning, middle and end. The double pages are coloured in by hand over the printed design.

Wrapping up

If you’re interested in typography and calligraphy, or the culture of Southeast Asia, or the history of the Malay Archipelago, or even if you just happen to be in town (maybe for JSConf.Asia or some CSS-related event), drop by the National Library and take a look.

It’s definitely one of my favourites and I didn’t even have to pay for it. Free admissions! I would have gladly paid to get in, seriously, and I’m the most cheapskate person I know 🤣.

Anyway, here’s a map to the library if you need directions. If you did go after reading this, tweet at me and let me know if you liked it as much as I did, if you want to. I mean, you do you, right?